Basilica fragment

The church fragment belongs to the basilica of the early 12th century. It once formed the three western bays of the central nave of the narthex of the Nazarius Basilica, which was largely destroyed during the Thirty Years’ War in 1621. It is likely that there were predecessor buildings in the area of the church fragment.

Building history of the church fragment

The theory of free-standing towers with a central structure developed by Friedrich Behn in the 1930s has been confirmed by our investigation. There was probably a predecessor building or buildings in the area of the church fragment. This is currently still being archaeologically investigated. For this reason, only the construction phases that can be traced in the existing masonry will be discussed here.

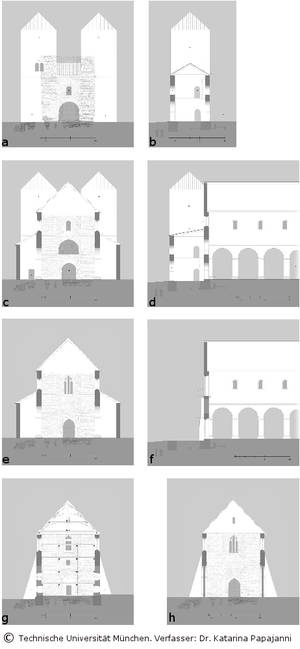

Figures 1 a and b show a reconstruction of the 1st construction phase of the east façade (today’s inner west wall) and a section to the north. Based on the findings, there is evidence of a large passageway opening in the central building.

In a 2nd construction phase (Figure 1 c and d), the towers were connected to the older church building to the east by a 4-bay sacred space with a basilical cross-section, the so-called antechurch. The three western bays of the nave of this narthex form today’s church fragment.

The fourth, narrower bay was demolished in the 18th century together with the east church. This construction phase can be linked to the 1140s by construction reports.

Our reconstruction differs from Behn’s findings in one important point: the large arch above the Gothic west portal (Fig. 2) does not belong to the 1st construction phase, as Behn assumed, but can be classified in the same construction phase as the ante-church on the basis of structural features. With the aforementioned arch, the upper floor of the central tower building was opened up as a kind of gallery to the central nave.

All of the building features can be dated to the early 11th century – both the architectural sculpture and the construction technique of the arcades and the stonework. Characteristic here is the stone processing with the tooth surface or the surface design with a herringbone pattern – each in different versions.

By comparing the mortar, further changes to the west wall can be dated to this time: The large opening of the 1st construction phase was reduced to a portal and, together with the arch above the gallery, a wall of small stone material was built between the towers. The gallery was probably given a shed roof, above which a window opening can be assumed.

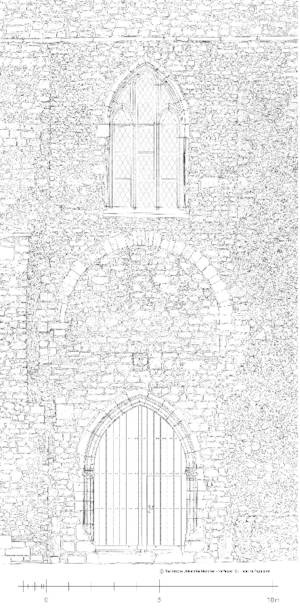

In the Gothic period, the west towers were demolished and the former inner east wall became the west façade, now designed with a new portal and a large tracery window – both can be dated to the early 14th century according to architectural-historical criteria (Fig. 1 e and f and Fig. 2).

The former church was largely destroyed during the Thirty Years’ War in 1621. Both sides of the arcade walls and the inner west wall, as well as the Gothic portal and the tracery window, show considerable fire damage as a result. After the destruction, the ruined monastery buildings were released as a demolition site for building materials.

In the Baroque period, the three western nave bays of the church ruins were given a new roof. The side aisles were demolished and the arcades walled up by this time at the latest. A new east wall was erected and the building was divided into four floors with a built-in timber construction. Equipped in this way, it was used as a fruit store and later as a tobacco barn (Fig. 1 g). The stands of the wooden construction were dendrochronologically dated to the winter of 1718/19 by the Otto-Friedrich University of Bamberg.

In the In the 19th century, the tracery window of the west façade was restored and at the beginning of the In the 20th century, the buttresses on the east façade were erected and the south-west buttresses repaired or rebuilt.

The extensive construction work in 1956/57 is documented in building files and photographic material. The plan at the time to present the church fragment as a ruin was not approved thanks to the objections of the state conservator Otto Müller.

Instead, the church fragment was restored in the form known to us today (2012) (Fig. 1 h).

Dr. Katarina Papajanni